Gynecologic Cancer Screening

Gynecologic Exams

The first step in detection of all gynecologic cancers is a basic gynecologic exam. Please join me in supporting #checkMeUp which simply asks that annual exams be available for all women. Many countries might take this for granted but in the UK, we must fight for earlier cancer detection and regular basic exams. Click on the image or link to be taken to the petition page, and hopefully also make a donation.

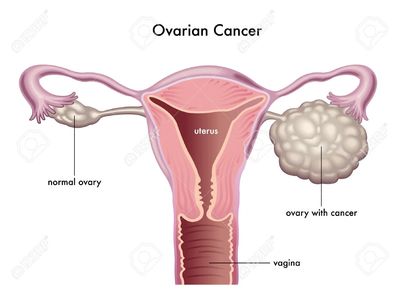

Example: Ovarian Cancer (more on ovarian cancer below)

A woman’s lifetime risk of developing ovarian cancer in western countries is about 1 in 50, and the prognosis is poor. The risk of testicular carcinoma is about 5 x less and the prognosis is excellent. Why?

- The ‘incessant ovulation’ hypothesis suggests that the number of ovulatory cycles increases the rate of cellular division associated with the repair of the surface epithelium after each ovulation, thereby increasing spontaneous mutations. Remember, each ovulation is a traumatic event with rupture of the covering of the ovary (epithelium) to release the egg. This would explain lower rates with pregnancy, and hormonal contraception that suppresses ovulation.

- Potential communication with outside world (through uterus and fallopian tubes) may make ovaries susceptible to inciting agents or retrograde flow of menstrual blood. This would explain substantially lower risk of ovarian cancer with tubal ligation, and increased risk of certain types of cancer with endometriosis.

- The ovaries are hidden, not available for examination, so that early detection is difficult.

Gynecologic Screening

Ovarian cancer is one example of why annual pelvic exams are important. It's also important for endometrial and cervical cancers, as well as more common benign conditions like fibroids, ovarian cyst, endometriosis, and PCOS. If there is any concern, transvaginal ultrasound can help (but not for cervical cancer).

Ovarian Cancer

Ovarian Cancer

Ovarian cancer is the sixth most common cancer among women after breast , bowel, lung,uterus (endometrium) and melanoma skin cancer. There are more than 7,000 new cases of ovarian cancer diagnosed every year in the UK. It is most common in post -menopausal women, although it can affect women of any age. The earlier ovarian cancer is diagnosed and treated, the better the chance of a cure. However, it's often not recognised until it's already spread and a cure is not possible. More than 70% of them are diagnosed at an advanced stage when the cancer has already spread.

Ovarian cancer begins in the ovary or the fallopian tube. The fallopian tube plays a very interesting role, probably in transport of inciting agents originating from the outside world through the vagina, cervix and uterus

Risk Factors

Your risk of developing ovarian cancer depends on many things including age, genetics, lifestyle and environmental factors. Of interest, it appears that the environment of the vagina and vulva affect the risk of ovarian cancer (for example, talc powder, or unhealthy vaginal bacteria). Inciting agents could travel through the cervix, uterus and fallopian tubes to reach the ovary or distal fallopian tube. This suggests that the ascending pathway is an important conduit for ovarian cancer. Conversely, tubal ligation (having tubes tied) or even hysterectomy may be protective by eliminating this potential path. The following factors can increase the risk of ovarian cancer:

Age

As with most cancers, the risk of developing ovarian cancer increases with age. More than 80% of ovarian cancer occur in women who are over 50 years of age.

Ovulatory Events

The risk of ovarian cancer increases with lifetime ovulation. Every time an egg is released, the surface of the ovary ruptures to let it out. The surface of the ovary is damaged during this process and needs to be repaired. Each time this happens, there’s a greater chance of abnormal cell growth during the repair. This incessant ovulation hypothesis proposes that repeated damage and repair to the ovarian surface increases ovarian cancer risk. This may be why the risk of ovarian cancer decreases if you take the contraceptive pill, or have multiple pregnancies or periods of breastfeeding as eggs aren’t released during this time. Women reporting menstrual cycle length >35 days had decreased risk of invasive ovarian cancer compared with women reporting cycle length ≤35 days [OR = 0.70; 95% confidence interval (CI) = 0.58-0.84]. Decreased risk of invasive ovarian cancer was also observed among women who reported irregular menstrual cycles compared with women with regular cycles (OR = 0.83; 95% CI = 0.76-0.89) However, other studies have observed increased risks of ovarian cancer among women with oligomenorrhea. Hormonal alterations in women with oligomenorrhea including elevated androgen levels, a common characteristic of women with PCOS, have been hypothesized to explain this increased ovarian cancer risk.

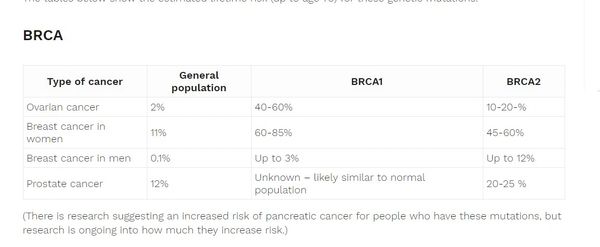

Genetic

Between 5 and 15 out of 100 ovarian cancers (5 to 15%) are caused by an inherited faulty gene. Inherited genes that increase the risk of ovarian cancer include faulty versions of BRCA1 and BRCA2 (see below). Faults in these genes also increase the risk of breast cancer.

Previous cancer

You have an increased risk of ovarian cancer if you've had breast cancer in the past. The risk is higher in women diagnosed with breast cancer at a younger age, and those with oestrogen receptor negative (ER negative) breast cancer.Women who had bowel cancer at a young age have an increased risk of ovarian cancer compared to the general population.The increase in risk of ovarian cancer after previous cancer is likely to be partly due to inherited faulty genes such as BRCA 1 and 2, and Lynch syndrome.

Using hormone replacement therapy (HRT)

Using HRT after the menopause increases the risk of ovarian cancer. In the UK, 4 in 100 (4%) ovarian cancers are linked to hormone replacement therapy (HRT) use. Remember that the increase in risk is small and HRT is helpful for many women with menopausal symptoms. Talk to your GP about the risks and benefits of taking HRT.

Bacteria in the Vagina

Recently, the type of bacteria in the vagina have been found to be associated with ovarian cancer. Levels of the friendly bacteria Lactobacilli were significantly lower in women with ovarian cancer or with BRCA1 gene mutations. The investigators believe that the balance of bacteria (known as a microbiome) in the vagina could provide a protective barrier to infections, stopping harmful bacteria from reaching the fallopian tubes and ovaries.

Smoking

Smoking can increase the risk of certain types of ovarian cancer such as mucinous ovarian cancer. The longer you have smoked, the greater the risk.

Other

Interestingly, use of talc powder has also been associated with ovarian cancer.

Medical conditions

Studies have shown that women with endometriosis or diabetes have an increased risk of ovarian cancer. Endometriosis may increase your risk of a rare sub- type of peritoneal cancer (a rare type of ovarian cancer).

Being overweight or obese

Having excess body fat is linked to an increase in risk of ovarian cancer. In diabetics, the increase in risk might be higher in those that use insulin.

Possible protective factors

The following factors may reduce your risk of ovarian cancer:

Taking the combined contraceptive pill

Taking the combined contraceptive pill at some point in your life reduces your risk of cancer of the ovary. Research has shown that the longer you take the pill, the more your risk is thought to be reduced. The reduction in risk lasts for tens of years after you stop taking the pill.

Having children and breastfeeding

Having children seems to reduce the risk of ovarian cancer. The more children you have, the lower the risk. Breastfeeding also reduces the risk of ovarian cancer.This reduction in risk may be because while you are pregnant or breastfeeding you're not ovulating (releasing eggs). The fewer times you ovulate in your lifetime the lower the risk of ovarian cancer.

Having a hysterectomy or having your tubes tied

Having your tubes tied is called tubal ligation. Studies have found that tubal ligation substantially lowers a woman's risk of ovarian cancer. Some suspect the reason may be that tubal ligation cuts off the ovaries' exposure to outside environmental factors that may increase the risk of ovarian cancer.

Until recently, most research has shown that having your womb removed (hysterectomy) may also reduce your risk of ovarian cancer. But this has become less clear in recent years and might depend on several factors including your age when you had the operation. Any reduction in risk may be greater for younger women. Researchers continue to study this area.

Other possible causes

Stories about potential causes are often in the media and it isn’t always clear which ideas are supported by evidence. There might be things you have heard of that we haven’t included here. This is because either there is no evidence about them or it is less clear.

Ovarian cancer symptoms - Key signs

If ovarian cancer symptoms are identified and the cancer diagnosed at an early stage, the outcome is more optimistic. However, because some of the symptoms of ovarian cancer are often the same as for other less serious conditions, such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) or pre-menstrual syndrome (PMS), it can be difficult to recognise the symptoms in the early stages – which is why most women are not diagnosed until the disease has spread.However, there are four main ovarian cancer symptoms that are more prevalent in women diagnosed with the condition. They are:

- increased abdominal size and persistent bloating (not bloating that comes and goes)

- persistent pelvic and abdominal pain

- unexplained change in bowel habits

- difficulty eating and feeling full quickly, or feeling nauseous

Other symptoms, such as back pain, needing to pass urine more frequently than usual, and pain during sex may be present in some women with the disease; however, it is most likely that these are not symptoms of ovarian cancer but may be the result of other conditions in the pelvic area. .

Types, Staging, Treatment

From CancerResearchUK.org

There are many types of ovarian cancer, with epithelial ovarian cancer being by far the most common form. Germ cell and stromal ovarian cancers are much less common.

- Epithelial ovarian cancer (epithelial ovarian tumours) – derived from cells on the surface of the ovary

- Fallopian tube cancer; we now know that many ovarian cancers begin here.

- Germ cell ovarian cancer (germ cell ovarian tumours) – derived from the egg-producing cells within the body of the ovary. This rare type of cancer more commonly affects teenagers.

- Stromal ovarian cancer (sex cord stromal tumours) – develops within the cells that hold the ovaries together.

- Cancers from other organs in the body can spread to the ovaries – metastatic cancers.

Some types are more common than others and affect women at different ages. Epithelial ovarian cancer is the most common type of ovarian cancer. Primary peritoneal cancer and fallopian tube cancer are similar to epithelial ovarian cancer and are treated in the same way.Rare types of ovarian cancer include sarcomas.

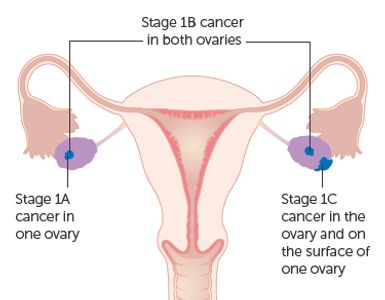

What are the stages of ovarian cancer?

Ovarian cancer is diagnosed at one of four stages. The stage describes how far the cancer has spread inside the body – the higher the stage the further the cancer has progressed.

Stage 1 ovarian cancer: The cancer is contained within one, or both of the ovaries. At this early stage, the cancer will not yet have started to spread. It is divided into 3 groups:

- stage 1C1 means the cancer is in one or both ovaries and the ovary ruptures (bursts) during surgery

- stage 1C2 means the cancer is in one or both ovaries and the ovary ruptures (bursts) before surgery or there is some cancer on the surface of an ovary

- stage 1C3 means the cancer is in one or both ovaries and there are cancer cells in fluid taken from inside your abdomen during surgery

Stage 2 ovarian cancer: The cancer will have started to spread from the ovaries to other parts of the pelvic region such as the womb, bladder and bowel.

Stage 3 ovarian cancer: By this stage, the cancer will have spread beyond the pelvic area into the abdominal cavity (a large space in your abdomen containing organs that include the liver, pancreas and kidneys) and lymph nodes.

Stage 4 ovarian cancer: The cancer has travelled some distance from the ovaries and into other parts of the body beyond the pelvic region. Organs such as the liver, lungs and brain may be affected. The earlier the cancer is diagnosed the easier it is to treat.

What are the grades of ovarian cancer?

Different types of tumours grow at different rates, and grading is the method used to predict how quickly a tumour is expected to develop. Like stages, ovarian cancer falls into one of four grades.

- Grade 0 ovarian cancer: Also known as borderline tumours as they are the least likely to be cancerous, Grade 0 ovarian cancer tumours are less aggressive, unlikely to spread, and are easier to cure.

- Grade 1 ovarian cancer: Grade 1 ovarian cancer tumours are low grade tumours that look very similar to normal tissue and grow very slowly.

- Grade 2 ovarian cancer: Grade 2 ovarian cancer tumours grow moderately quickly and are sometimes referred to as intermediate grade tumours.

- Grade 3 ovarian cancer: Grade 3 ovarian cancer tumours grow quickly and in a disorganised way. They are the most aggressive type of cancer.

Treatment Currently, the available treatment is a combination of chemotherapy and surgery. The main treatment is surgery. The specialist doctors consider several factors when deciding what type of treatment you need. These include;

- whether you have stage 1A, 1B or 1C ovarian cancer

- the grade of your cancer

- the type of cells the cancer started in

- your age and whether you want any more children

- other health conditions you have

After surgery, your doctor might suggest you have chemotherapy if you have:

- stage 1c ovarian cancer

- a high grade (grade 3) cancer

This is called adjuvant chemotherapy and aims to lower the risk of your cancer coming back.

Even after successful treatment, there's a high chance the cancer will come back within the next few years. Despite months of aggressive treatment involving surgery and chemotherapy, about 85 percent of women with high-grade wide-spread ovarian cancer will have a recurrence of their disease. This leads to further treatment, but never to a cure. About 15 percent of patients, however, do not have a recurrence. Most of those women remain disease free for years. Overall, around half of women with ovarian cancer will live for at least 5 years after diagnosis, and about 1 in 3 will live at least 10 years.

Substantial progress has been made in understanding ovarian cancer at the molecular and cellular level. Significant improvement in 5-year survival has been achieved through cytoreductive surgery, combination platinum-based chemotherapy, and more effective treatment of recurrent cancer, and there are now more than 280,000 ovarian cancer survivors in the United States. Despite these advances, long-term survival in late-stage disease has improved little over the last 4 decades. Poor outcomes relate, in part, to late stage at initial diagnosis, intrinsic drug resistance, and the persistence of dormant drug-resistant cancer cells after primary surgery and chemotherapy.

Research

Wild-type isocitrate dehydrogenase I (IDH1) is the only TCA cycle enzyme upregulated in both adherent and spheroid conditions and is associated with reduced progression-free survival. suggest that increased IDH1 activity is an important metabolic adaptation in HGSC and that targeting wild-type IDH1 in HGSC alters the repressive histone epigenetic landscape to induce senescence

Implications: Inhibition of IDH1 may act as a novel therapeutic approach to alter both the metabolism and epigenetics of HGSC as a prosenescent therapy. REF

Doctors use a simple 1 to 4 staging system for ovarian cancer. It is called the FIGO system after its authors - the International Federation of Gynaecological Oncologists.

One story.

BRCA Mutations and Other Markers

Ultrasound and genetic markers remain the best hope for detection. CA125 levels can also be followed but are considered less reliable than ultrasound.

A BRCA mutation is a mutation in either of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes, which are tumour suppressor genes. Hundreds of different types of mutations in these genes have been identified, some of which have been determined to be harmful, while others have no proven impact.

Having relatives with ovarian cancer does not necessarily mean that you have a faulty inherited gene in the family. The cancers could have happened by chance. But women with a mother or sister diagnosed with ovarian cancer have around 3 times the risk of ovarian cancer compared to women without a family history.If you have two or more close relatives (mother, sister or daughter) who developed ovarian cancer or breast cancer, your risk of also developing the condition may be increased.If your relatives developed cancer before the age of 50, it’s more likely it was the result of an inherited faulty gene.You may be at a high risk of having a faulty gene if you have:

- One relative diagnosed with ovarian cancer at any age and at least two close relatives with breast cancer whose average age is under 60; or alternatively at least one close relative with breast cancer under the age of 50. All of these relatives should be on the same side of your family (either your mother’s OR father’s side)

- Two relatives from the same side of the family diagnosed with ovarian cancer at any age.

MYC gene

MYC proto-oncogene, bHLH transcription factorThis gene is a proto-oncogene and encodes a nuclear phosphoprotein that plays a role in cell cycle progression, apoptosis and cellular transformation. The encoded protein forms a heterodimer with the related transcription factor MAX. This complex binds to the E box DNA consensus sequence and regulates the transcription of specific target genes. Amplification of this gene is frequently observed in numerous human cancers

Ovarian Masses by Ultrasound

Dermoid

The most common benign tumor of the ovary. Not cancerous.

A dermoid, or dermoid cyst grows from primitive embryonal cells. Most dermoids are entirely asymptomatic- women are not aware they have them. They are usually discovered during a pelvic exam or a pelvic ultrasound performed for other reasons. However, some tumors, like dermoids, may be associated with pelvic pain if they cause torsion, or partial torsion of the ovary.

Endometrioma

The most common reason for a persistent ovarian cyst or mass that is not a simple cyst. This is not a cancer

Borderline Ovarian Cancer

Mural nodules are very suspicious

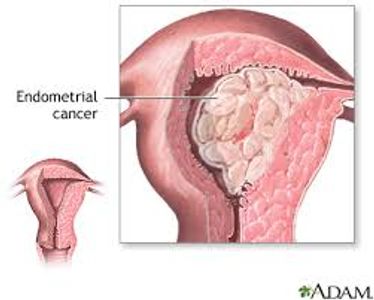

Endometrial Cancer

Endometrial Cancer

From TeachMeObgyn.com Also see blog post

Endometrial cancer is the fourth most common cancer affecting women in the UK, and the most common gynaecological cancer in the developed world.The incidence of this malignancy has risen by approximately 40% over the past 20 years – which has been attributed to an increase in obesity during this time period.In the UK, the peak incidence of endometrial cancer is between 65 and 75 years of age, although ~5% of women affected are under the age of 40.

The most common form of endometrial cancer is adenocarcinoma, a neoplasia of epithelial tissue that has glandular origin and/or glandular characteristics.Most cases of adenocarcinoma are caused by stimulation of the endometrium by oestrogen, without the protective effects of progesterone (termed ‘unopposed oestrogen’).Progesterone is produced by the corpus luteum after ovulation. Scenarios in which women may have experienced a longer period of anovulation are thought to predispose to developing malignancy.Unopposed oestrogen can also cause endometrial hyperplasia. This in itself is not malignancy, but can predispose to atypia, a precancerous state.

Risk Factors

Anovulation

Women who experience a prolonged period of anovulation – and therefore exposure to ‘unopposed’ oestrogen – are at a greater risk of developing endometrial cancer:

- Early menarche and/or late menopause– at the extremes of menstrual age, menstrual cycles are more likely to be anovulatory.

- Low parity – just under 1/3 of women developing endometrial cancer are nulliparous. With each pregnancy, the risk of endometrial cancer decreases.

- Polycystic ovarian syndrome – with oligomenorrhoea, cycles are more likely to be anovulatory.

- Hormone replacement therapy with oestrogen alone.

- Tamoxifen use

Age

The peak incidence of endometrial cancer is between 65 and 75 years. Prior to the age of 45, the risk of endometrial cancer is low.

Obesity

Approximately 40% of endometrial cancer cases are thought to be linked to obesity.The greater the amount of subcutaneous fat, the faster the rate of peripheral aromatisation of androgens to oestrogen – which increases unopposed oestrogen levels in post-menopausal women.

Hereditary Factors

Genetic conditions that predispose to cancer, such as hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer (Lynch syndrome), are a risk factor for developing endometrial cancer.

Staging And Treatment

From TeachMeObgyn.com

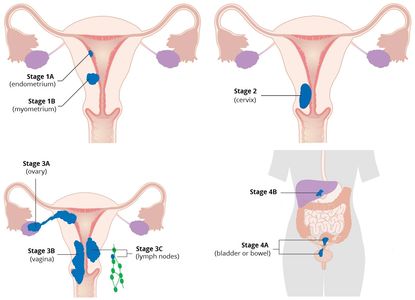

FIGO Staging

The most widely used staging system is that from the International Federation of Obstetrics and Gynaecology (FIGO):

- Stage I – Carcinoma confined to within uterine body.

- Stage II – Carcinoma may extend to cervix but is not beyond the uterus.

- Stage III – Carcinoma extends beyond uterus but is confined to the pelvis.

- Stage IV – Carcinoma involves bladder or bowel, or has metastasised to distant sites.

Management

Endometrial Hyperplasia

Non-malignant ‘simple’ or ‘complex’ hyperplasia without atypia can be treated with progestogens e.g Mirena IUS. Surveillance biopsies should be performed to identify any progression to atypia or malignancy.Atypical hyperplasia, which has the highest rate of progression to malignancy, should be treated with total abdominal hysterectomy + bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. If this surgery is contra-indicated, regular surveillance biopsies should be performed.

Endometrial Carcinoma

The management typically offered in endometrial carcinoma is dependent on the stage of the cancer:

- Stage I – Total hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. Peritoneal washings should also be taken. Traditionally, this has been performed as an open procedure, but laparoscopic surgery is increasingly performed.

- 75% of women present with stage I disease, and this has a very good 5-year survival rate of 90%.

- Stage II – Radical hysterectomy (whereby vaginal tissue surrounding the cervix is also removed, alongside the supporting ligaments of the uterus), and assessment and removal of pelvic lymph nodes (lymphadenectomy).

- Women with confirmed carcinoma stage Ic or II may be offered adjuvant radiotherapy.

- Stage III – Maximal de-bulking surgery (if possible)

- Additional chemotherapy is usually given prior to radiotherapy.

- Stage IV – Maximal de-bulking surgery (if possible)

- In many stage IV patients, a palliative approach is preferred, e.g. with low dose radiotherapy, or high dose oral progestogens.

Detection

A transvaginal ultrasound scan is the most widely used first-line investigation. 96% of women with endometrial cancer will have an endometrial thickness of >5mm on ultrasound.If an endometrial thickness of >4mm in a postmenopausal woman is identified, an endometrial biopsy should be obtained. This can be performed at an outpatient appointment, often with a Pipelle biopsy. Histology from the biopsy can confirm the presence of hyperplasia, with or without atypia, or malignancy.If the gynaecologist deems the case high risk, such as with heavy bleeding, multiple risk factors or very thickened endometrium on ultrasound (or the patient is unable to tolerate outpatient sampling), hysteroscopy with biopsy may be performed – either as an outpatient or under anaesthetic.If the endometrium is <4mm and appears normal on ultrasound, it is reasonable to defer endometrial sampling as the risk of cancer is low. However, if they continue to have abnormal bleeding then sampling may be indicated.If malignancy is confirmed, an MRI or CT scan may be used for staging.

Cervical Cancer

Cervical Cancer

From EveAppeal.org.uk

Cervical cancer is cancer of the cervix (also known as the neck of the womb) which connects a woman's womb and her vagina. Cervical cancer can affect women of all ages but affects women primarily 30 - 45 years of age. It is very rare in women under 25 years of age. In the UK we have a very successful cervical screening programme which is estimated to save over 4,000 lives each year.

How does it develop?

Nearly all squamous cervical cancers are caused by a common sexually transmitted infection called human papillomavirus (HPV). This is why the UK government is vaccinating girls at an early age before they are potentially exposed to the HPV virus (i.e. before they experience sexual activity). Sex is a normal, healthy activity, and the wearing of condoms is advised to protect both partners from unwanted pregnancies and reduce exposure to HPV, as well as other transmissible conditions.Most women will contract HPV at some stage during their life, but this usually clears up on its own without the need for any treatment.HPV is a group of viruses, of which there are more than 100 different types. It is spread during sexual intercourse and other types of sexual activity (such as skin-to-skin contact of the genital areas).If the body is unable to clear the virus, there is a risk of abnormal cells developing, which could become cancerous over time.Cervical cancer can affect women of all ages, but is most common in women aged 30 – 45; although in rare cases can occur in women under 25.

Key signs of cervical cancer - symptoms

The symptoms of cervical cancer aren’t always obvious, it may not cause any symptoms at all until it’s reached an advanced stage. Some women do not experience any signs of cervical cancer at all.This is why it’s very important that you attend all of your cervical screening appointments.

Unusual bleedingIn most cases, vaginal bleeding is the first of the cervical cancer symptoms to be noticeable. It often occurs after having sex.Bleeding at any other time, other than your expected monthly period, is also considered unusual, this also includes bleeding after the menopause.

Other symptomsOther signs of cervical cancer may include pain and discomfort during sex and an unpleasant smelling vaginal discharge.However, the vast majority of women with the cervical cancer symptoms listed above do not have cervical cancer, and are far more likely to be experiencing other conditions, such as infections.

Risk Factors

The fact that HPV infection is very common but cervical cancer is relatively uncommon suggests that only a very small proportion of women are vulnerable to the effects of an HPV infection. There appear to be additional risk factors that affect a woman’s chance of developing cancer of the cervix. These include:

- Smoking – women who smoke are twice as likely to develop cervical cancer as women who don’t; this may be caused by the harmful effects of chemicals found in tobacco on the cells of the cervix.

- Immunosuppression drugs – women who are on Immunosuppression drugs (reduces the strength of the body’s immune system) can be at increased risk of developing cervical cancer.

How is it diagnosed?

You’ll be referred to a gynaecologist if the results of your cervical screening test suggest that there are abnormalities in the cells of your cervix. However, in most cases, the abnormalities do not mean you have cancer of the cervix.You may also be referred to a gynaecologist if you have abnormal vaginal bleeding, or other worrying cervical cancer symptoms, such as if your GP has noticed a growth inside your cervix during an examination.Additionally, your gynaecologist or a specialist nurse may perform a colposcopy – an examination to look for abnormalities in your cervix. During a colposcopy, a small microscope with a light source at the end (colposcope) is used. As well as examining your cervix, your gynaecologist may remove a small tissue sample (biopsy) so that it can be checked under a microscope for cancerous cells.

Cervical Cancer Treatment

Treatment for cervical cancer depends on the size of the cancer cell collection and the shape of it.The prospect of a complete cure is good for cervical cancer diagnosed at an early stage, this decreases the further the cancer has grown into or around the cervix.

Removing abnormal cellsIf your screening results show that you don’t have cancer of the cervix, but there are biological changes that could turn cancerous in the future, a number of treatment options are available. These include:

- Large loop excision of the transformation zone (LLETZ) – the abnormal cells are removed under local anaesthetic.

- Cone biopsy – the area of abnormal tissue, in the shape of a cone, is removed during surgery

SurgeryThere are three main types of surgery for cervical cancer:

- Radical trachelectomy – the cervix, surrounding tissue and the upper part of the vagina are removed, but the body of the womb is left in place. This cervical cancer treatment is only a suitable if the diagnosis is made at a very early stage. In addition lymph nodes that are related to this area are sampled to check for microscopic spread.

- Hysterectomy – the cervix and womb are removed, which is recommended for early cervical cancer, and in some cases a course of radiotherapy may follow to help prevent the cancer coming back.

- After Pelvic Exoneration – a major operation that’s usually only recommended when cervical cancer returns what was thought to be a previously successful course of treatment, in which the cervix, vagina, womb, bladder, ovaries, fallopian tubes and rectum are removed.

Radiotherapy is also considered as part of cervical cancer treatment; an alternative to surgery it has a similar cure rate and has the advantage of avoiding an operation when the cancer is close to the bladder or colon.

Cervical Cancer is a Prevental Disease

HPV Vaccine for Children

"HPV vaccine programme in schools 'could wipe out cervical cancer for good'," reports the Mail Online.Researchers in Canada summarised 65 studies from 14 countries that have introduced HPV vaccination since it became available a decade ago. The vaccine targets several strains of human papilloma virus (HPV), including strains 16 and 18 which cause most cervical cancers. HPV can also cause genital warts and some other types of cancer.Researchers compared infection rates before and after introduction of the vaccine for both teens (13 to 19 years) and young adults (20 to 24 years). HPV 16 or 18 infections fell by 83% for teenage girls and 66% for young women 5 to 8 years after vaccine introduction.Genital wart diagnoses fell for both teenage girls and boys and young men and women. The numbers of teenage girls and young women with pre-cancerous cells found in the cervix also fell 5 to 9 years after the vaccine was introduced – a good sign, as this suggests the vaccine really will reduce the number of women getting cervical cancer.In the UK, girls aged 12 to 13 are offered the first dose of the vaccine at school, with a second dose 6 to 12 months later. Boys aged 12 to 13 will be offered the vaccine from September this year.The researchers found that the greatest benefits of vaccination were seen in countries where more than 50% of the targeted population was vaccinated, and where girls were offered vaccination at multiple ages, to catch up on the older girls who had missed the introduction of the vaccine.If vaccination programmes can lead to the eradication of HPV, in the same way that they did for smallpox, then this should result in a subsequent eradication of cervical cancer.

There’s a major new cancer-prevention effort taking place and the target is young boys under the age of twelve. The National Health System in Britain, or NHS, is now mandating that schools offer vaccination against the Human Papilloma Virus (HPV) for all boys. The vaccinations are to be given at the age of twelve and the goal is to keep boys from developing head and neck cancers, anal cancer, and penile cancer– all of which are linked to HPV.

If you are an American and you’ve had sex, there’s about an 80 percent chance that you have HPV. In Britain, one in three people currently have HPV, and 90 percent of people will come into contact with HPV in their lives.

Vaccinations to protect against HPV have been primarily administered to women, because HPV is often linked to cervical and vaginal cancers, but they can cause cancer in men as well.

Practice Advisory: FDA Approval of 9-valent HPV Vaccine for Use in Women and Men Age 27-45

On October 5, 2018 the FDA approved the use of the 9-valent HPV vaccine in women and men aged 27 through 45 years (1). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) reviewed the available data at its February 2019 and June 2019 in-person meetings. On June 26, 2019, ACIP voted to recommend shared clinical decision making for persons aged 27 through 45 years when considering the 9-valent HPV vaccine. This recommendation is for women who have not previously received an HPV vaccine series and who are at risk for acquisition of HPV. HPV vaccination is most effective when given during the recommended ages of 11-12 years

Vulval Cancer

Vulval Cancer

From EveAppeal.org.uk

Cancer of the vulva (also called vulvar cancer or vulval cancer) is one of the rarer cancers with just over 1,000 cases diagnosed in the UK each year.

What is cancer of the vulva?

The vulva describes a woman’s external genitals. It includes the soft tissue (lips) surrounding the vagina (labia minora and labia majora), the clitoris (sexual organ that when stimulated can achieve sexual climax), and the Bartholin’s glands, two small glands each side of the vagina that secrete a musk like fluid to enhance lubrication.

Around 80% of vulval cancers are diagnosed in women over 60; however we are increasingly seeing more and more women being diagnosed at a younger age.

How does it develop?

Skin conditions that cause inflammation MAY develop into an early vulval cancer. The two most common of these being vulval intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN) and Lichen Sclerosis.

There are a number of rare sub-types of vulval cancer, including mucosal melanoma, which can predict how the cancer might behave. You may find that you are cared for by gynaecologists and melanoma specialists to give you the best all-round support.

VIN does not mean you have cancer of the vulva – it is the stage before a potential cancer may develop. Some of these cell changes will go away without the need for any treatment; however, finding these abnormal cells early can help to prevent vulvar cancer.

Vulvar Cancer symptoms - Key signs

The signs and symptoms of vulva cancer can include:

- a lasting itch

- pain or soreness

- thickened, raised, red, white or dark patches on the skin of the vulva

- an open sore or growth visible on the skin

- a mole on the vulva that changes shape or colour

- a lump or swelling in the vulva

All these symptoms can be caused by other more common conditions, such as infection, but if you have any of these, you should see your GP. It is unlikely that your symptoms are caused by a serious problem but it is important to be checked out… remember non- cancerous conditions can be uncomfortable and so much better when treated!

Risk Factors

Increasing age

The risk of developing cancer of the vulva increases as you get older. Most cases develop in women aged 65 or over, although women under 50 can be affected.

Vulval intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN)

Vulval intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN) is potentially a pre-cancerous condition. This means there are changes to certain cells in the vulva that aren’t cancerous, but could become a cancer at a later date. This is a gradual process that usually takes well over 10 years.

Symptoms of vulva cancer are similar to those of VIN, and can include persistent itchiness of the vulva and raised discoloured patches. See your GP if you have these symptoms.

There are two types of VIN:

- Usual or undifferentiated VIN – this typically affects women under 50 and is thought to be caused by an HPV infection

- Differentiated VIN (dVIN) – this is a rarer type, usually affecting women over 60, associated with skin conditions that affect the vulva, and is more likely to be associated with cancer.

Human papilloma virus (HPV)

HPV is a group of viruses, rather than a single virus, of which there are more than 100 different types. It is spread during sexual intercourse and other types of sexual activity (such as skin-to-skin contact of the genital areas).

There are many different types of HPV, and most people are infected with the virus at some time during their lives. In most cases, the virus is cleared by the body without causing any harm and doesn’t lead to further problems.

However, HPV is present in at least 40% of women with vulvar cancer, which suggests it may increase your risk of developing the condition. HPV is known to cause changes in the cells of the cervix, which can lead to cervical cancer. It’s thought the virus could have a similar effect on the cells of the vulva, which is known as VIN.

Skin conditions

Several skin conditions can affect the vulva. In a small number of cases these are associated with an increased risk of vulva cancer.

Smoking

Smoking increases your risk of developing VIN and vulval cancer. This may be because smoking makes the immune system less effective, and less able to clear the HPV virus from your body and more vulnerable to the effects of the virus.

How is it diagnosed?

Your doctor will examine your skin to determine whether to refer you to a gynaecologist or a dermatologist (skin specialist).

Referral to a gynaecologist

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends that GPs consider referring a woman who has an unexplained vulval lump or ulcer, or unexplained bleeding.

The gynaecologist will ask about your symptoms and examine your vulva again, and they may recommend a test called a biopsy.

Biopsy

A biopsy is where a small sample of tissue is removed so it can be examined under a microscope to determine what the skin cell changes are due to.

Your doctor will usually see you 7 to 10 days later to discuss the results with you.

Treatment

Treatment for vulval cancer depends on factors such as how far the cancer has spread from the area it started. Vulva cancer can be treated by surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy or a combination of all three.

Surgery to remove vulvar cancer

In most cases, the treatment plan will involve some form of surgery. The type of surgery will depend on the stage of the cancer. The principle of surgery being to remove all diseased skin with a margin of healthy skin all around it and also to check for potential spread.

There are three surgical options to treat cancer of the vulva:

- Radical wide local excision – the cancerous tissue from the vulva is removed, as a well as a margin of healthy tissue, at least 1cm wide, to prevent spread to healthy tissue.

- Radical partial vulvectomy – a larger section of the vulva is removed, this may include the labia and the clitoris

- Radical vulvectomy – the whole vulva is removed, including the inner and outer labia, and possibly the clitoris and removal of some lymph nodes

- In some centres they will use sentinel node surgery, where a safe radio – active dye is injected into the affected area. During surgery this dye will highlight any potential spread into lymph nodes that will guide the surgeon to selectively remove to be tested, increasing accuracy of diagnosis and reducing the long term side effect of lymph node surgery, lymphoedema.

Breast Cancer

Breast Cancer

Breast cancer is the most common type of cancer in the UK.

Most women who get it (8 out of 10) are over 50, but younger women, and in rare cases, men, can also get breast cancer.

If it's treated early enough, breast cancer can be prevented from spreading to other parts of the body.

Breast cancer is cancer that develops in breast cells. Typically, the cancer forms in either the lobules or the ducts of the breast. Lobules are the glands that produce milk, and ducts are the pathways that bring the milk from the glands to the nipple. Cancer can also occur in the fatty tissue or the fibrous connective tissue within your breast.

The uncontrolled cancer cells often invade other healthy breast tissue and can travel to the lymph nodes under the arms. The lymph nodes are a primary pathway that help the cancer cells move to other parts of the body.

Breast cancer symptoms

In its early stages, breast cancer may not cause any symptoms. In many cases, a tumor may be too small to be felt, but an abnormality can still be seen on a mammogram. If a tumor can be felt, the first sign is usually a new lump in the breast that was not there before. However, not all lumps are cancer.

Each type of breast cancer can cause a variety of symptoms. Many of these symptoms are similar, but some can be different. Symptoms for the most common breast cancers include:

- a breast lump or tissue thickening that feels different than surrounding tissue and has developed recently

- breast pain

- red, pitted skin over your entire breast

- swelling in all or part of your breast

- a nipple discharge other than breast milk

- bloody discharge from your nipple

- peeling, scaling, or flaking of skin on your nipple or breast

- a sudden, unexplained change in the shape or size of your breast

- inverted nipple

- changes to the appearance of the skin on your breasts

- a lump or swelling under your arm

If you have any of these symptoms, it doesn’t necessarily mean you have breast cancer. For instance, pain in your breast or a breast lump can be caused by a benign cyst. Still, if you find a lump in your breast or have other symptoms, you should see your doctor for further examination and testing.

Types, Staging, Treatment

Types of breast cancer

There are several types of breast cancer, and they are broken into two main categories: “invasive” and “noninvasive,” or in situ. While invasive cancer has spread from the breast ducts or glands to other parts of the breast, noninvasive cancer has not spread from the original tissue.

These two categories are used to describe the most common types of breast cancer, which include:

- Ductal carcinoma in situ. Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) is a noninvasive condition. With DCIS, the cancer cells are confined to the ducts in your breast and haven’t invaded the surrounding breast tissue.

- Lobular carcinoma in situ. Lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS) is cancer that grows in the milk-producing glands of your breast. Like DCIS, the cancer cells haven’t invaded the surrounding tissue.

- Invasive ductal carcinoma. Invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC) is the most common type of breast cancer. This type of breast cancer begins in your breast’s milk ducts and then invades nearby tissue in the breast. Once the breast cancer has spread to the tissue outside your milk ducts, it can begin to spread to other nearby organs and tissue.

- Invasive lobular carcinoma. Invasive lobular carcinoma (ILC) first develops in your breast’s lobules and has invaded nearby tissue.

Other, less common types of breast cancer include:

- Paget disease of the nipple. This type of breast cancer begins in the ducts of the nipple, but as it grows, it begins to affect the skin and areola of the nipple.

- Phyllodes tumor. This very rare type of breast cancer grows in the connective tissue of the breast. Most of these tumors are benign, but some are cancerous.

- Angiosarcoma. This is cancer that grows on the blood vessels or lymph vessels in the breast.

The type of cancer you have determines your treatment options, as well as your likely long-term outcome. Learn more about types of breast cancer.

Inflammatory breast cancer

Inflammatory breast cancer (IBC) is a rare but aggressive type of breast cancer. IBC makes up only between 1 and 5 percent of all breast cancer cases.

With this condition, cells block the lymph nodes near the breasts, so the lymph vessels in the breast can’t properly drain. Instead of creating a tumor, IBC causes your breast to swell, look red, and feel very warm. A cancerous breast may appear pitted and thick, like an orange peel.

IBC can be very aggressive and can progress quickly. For this reason, it’s important to call your doctor right away if you notice any symptoms. Find out more about IBC and the symptoms it can cause.

Triple-negative breast cancer

Triple-negative breast cancer is another rare disease type, affecting only about 10 to 20 percent of people with breast cancer. To be diagnosed as triple-negative breast cancer, a tumor must have all three of the following characteristics:

- It lacks estrogen receptors. These are receptors on the cells that bind, or attach, to the hormone estrogen. If a tumor has estrogen receptors, estrogen can stimulate the cancer to grow.

- It lacks progesterone receptors. These receptors are cells that bind to the hormone progesterone. If a tumor has progesterone receptors, progesterone can stimulate the cancer to grow.

- It doesn’t have additional HER2 proteins on its surface. HER2 is a protein that fuels breast cancer growth.

If a tumor meets these three criteria, it’s labeled a triple-negative breast cancer. This type of breast cancer has a tendency to grow and spread more quickly than other types of breast cancer.

Triple-negative breast cancers are difficult to treat because hormonal therapy for breast cancer is not effective. For patients with advanced triple-negative breast cancer with BRCA1/2mutations, poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors show clear benefit, as do the older platinum agents. Learn about treatments and survival rates for triple-negative breast cancer.

Metastatic breast cancer

Metastatic breast cancer is another name for stage 4 breast cancer. It’s breast cancer that has spread from your breast to other parts of your body, such as your bones, lungs, or liver.

This is an advanced stage of breast cancer. Your oncologist (cancer doctor) will create a treatment plan with the goal of stopping the growth and spread of the tumor or tumors. Learn about treatment options for metastatic cancer, as well as factors that affect your outlook.

Breast cancer stages

Breast cancer can be divided into stages based on how large the tumor or tumors are and how much it has spread. Cancers that are large and/or have invaded nearby tissues or organs are at a higher stage than cancers that are small and/or still contained in the breast. In order to stage a breast cancer, doctors need to know:

- if the cancer is invasive or noninvasive

- how large the tumor is

- whether the lymph nodes are involved

- if the cancer has spread to nearby tissue or organs

Breast cancer has five main stages: stages 0 to 5.

Stage 0 breast cancer

Stage 0 is DCIS. Cancer cells in DCIS remain confined to the ducts in the breast and have not spread into nearby tissue.

Stage 1 breast cancer

- Stage 1A: The primary tumor is 2 centimeters wide or less and the lymph nodes are not affected.

- Stage 1B: Cancer is found in nearby lymph nodes, and either there is no tumor in the breast, or the tumor is smaller than 2 cm.

Stage 2 breast cancer

- Stage 2A: The tumor is smaller than 2 cm and has spread to 1–3 nearby lymph nodes, or it’s between 2 and 5 cm and hasn’t spread to any lymph nodes.

- Stage 2B: The tumor is between 2 and 5 cm and has spread to 1–3 axillary (armpit) lymph nodes, or it’s larger than 5 cm and hasn’t spread to any lymph nodes.

Stage 3 breast cancer

- Stage 3A:

- The cancer has spread to 4–9 axillary lymph nodes or has enlarged the internal mammary lymph nodes, and the primary tumor can be any size.

- Tumors are greater than 5 cm and the cancer has spread to 1–3 axillary lymph nodes or any breastbone nodes.

- Stage 3B: A tumor has invaded the chest wall or skin and may or may not have invaded up to 9 lymph nodes.

- Stage 3C: Cancer is found in 10 or more axillary lymph nodes, lymph nodes near the collarbone, or internal mammary nodes.

Stage 4 breast cancer

Stage 4 breast cancer can have a tumor of any size, and its cancer cells have spread to nearby and distant lymph nodes as well as distant organs.

The testing your doctor does will determine the stage of your breast cancer, which will affect your treatment.

Breast cancer treatment

Your breast cancer’s stage, how far it has invaded (if it has), and how big the tumor has grown all play a large part in determining what kind of treatment you’ll need.

To start, your doctor will determine your cancer’s size, stage, and grade (how likely it is to grow and spread). After that, you can discuss your treatment options. Surgery is the most common treatment for breast cancer. Many women have additional treatments, such as chemotherapy, targeted therapy, radiation, or hormone therapy.

Surgery

Several types of surgery may be used to remove breast cancer, including:

- Lumpectomy. This procedure removes the tumor and some surrounding tissue, leaving the rest of the breast intact.

- Mastectomy. In this procedure, a surgeon removes an entire breast.In a double mastectomy, both breasts are removed.

- Sentinel node biopsy. This surgery removes a few of the lymph nodes that receive drainage from the tumor. These lymph nodes will be tested. If they don’t have cancer, you may not need additional surgery to remove more lymph nodes.

- Axillary lymph node dissection. If lymph nodes removed during a sentinel node biopsy contain cancer cells, your doctor may remove additional lymph nodes.

- Contralateral prophylactic mastectomy. Even though breast cancer may be present in only one breast, some women elect to have a contralateral prophylactic mastectomy. This surgery removes your healthy breast to reduce your risk of developing breast cancer again.

Radiation therapy

With radiation therapy, high-powered beams of radiation are used to target and kill cancer cells. Most radiation treatments use external beam radiation. This technique uses a large machine on the outside of the body.

Advances in cancer treatment have also enabled doctors to irradiate cancer from inside the body. This type of radiation treatment is called brachytherapy. To conduct brachytherapy, surgeons place radioactive seeds, or pellets, inside the body near the tumor site. The seeds stay there for a short period of time and work to destroy cancer cells.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is a drug treatment used to destroy cancer cells. Some people may undergo chemotherapy on its own, but this type of treatment is often used along with other treatments, especially surgery.

In some cases, doctors prefer to give patients chemotherapy before surgery. The hope is that the treatment will shrink the tumor, and then the surgery will not need to be as invasive. Chemotherapy has many unwanted side effects, so discuss your concerns with your doctor before starting treatment.

Hormone therapy

If your type of breast cancer is sensitive to hormones, your doctor may start you on hormone therapy. Estrogen and progesterone, two female hormones, can stimulate the growth of breast cancer tumors. Hormone therapy works by blocking your body’s production of these hormones, or by blocking the hormone receptors on the cancer cells. This action can help slow and possibly stop the growth of your cancer.

Medications

Certain treatments are designed to attack specific abnormalities or mutations within cancer cells. For example, Herceptin (trastuzumab) can block your body’s production of the HER2 protein. HER2 helps breast cancer cells grow, so taking a medication to slow the production of this protein may help slow cancer growth.

Mammography and Screening

Diagnosis of breast cancer

To determine if your symptoms are caused by breast cancer or a benign breast condition, your doctor will do a thorough physical exam in addition to a breast exam. They may also request one or more diagnostic tests to help understand what’s causing your symptoms.

Tests that can help diagnose breast cancer include:

- Mammogram. The most common way to see below the surface of your breast is with an imaging test called a mammogram. Many women aged 40 and older get annual mammograms to check for breast cancer. If your doctor suspects you may have a tumor or suspicious spot, they will also request a mammogram. If an abnormal area is seen on your mammogram, your doctor may request additional tests.

- Ultrasound. A breast ultrasound uses sound waves to create a picture of the tissues deep in your breast. An ultrasound can help your doctor distinguish between a solid mass, such as a tumor, and a benign cyst.

Your doctor may also suggest tests such as an MRI or a breast biopsy

From Johns Hopkins (USA) regarding 6 myths of mammograms

Myth #1: I don’t have any symptoms of breast cancer or a family history, so I don’t need to worry about having an annual mammogram.

Fact: The American College of Radiology recommends annual screening mammograms for all women over 40, regardless of symptoms or family history. “Early detection is critical,” says Dr. Sarah Zeb. “If you wait to have a mammogram until you have symptoms of breast cancer, such as a lump or discharge, at that point the cancer may be more advanced .” According to the American Cancer Society, early-stage breast cancer has a five-year survival rate of 99 percent. Later-stage cancer has a survival rates of 27 percent.More than 75 percent of women who have breast cancer have no family history.

Myth #2: A mammogram will expose me to an unsafe level of radiation.

Fact: “While a mammogram does use radiation, it is a very small amount and is within the medical guidelines,” says Dr. Zeb. Because mammography is a screening tool, it is highly regulated by the Food and Drug Administration, Mammography Quality and Standards Act and other governing organizations, like the American College of Radiology. A mammogram is safe as long as the facility you go to is certified by the regulating agencies. There is constant background radiation in the world that we are exposed to every day. The radiation dose from a mammogram is equal to about two months of background radiation for the average woman.

Myth #3: A 3-D mammogram is the same as a traditional mammogram.

Fact: Three-dimensional mammography, or tomosynthesis, is the most modern screening and diagnostic tool available for early detection of breast cancer. Compared to a standard 2-D mammogram, a 3-D mammogram displays more images of the breast and in thin sections of breast tissue. “3-D mammograms provide us greater clarity and the ability to determine the difference between overlapping normal tissue and cancer,” says Dr. Zeb. “With 3-D mammography, the data show a 40 percent increase in detecting early cancer and a 40 percent decrease in false alarms or unnecessary recalls from screening.”

Myth #4: If I have any type of cancer in my breast tissue, a screening mammogram is guaranteed to find it.

Fact: “While annual mammograms are very important for women, there are limitations,” says Dr. Zeb. This is mostly due to dense breast tissue — the denser the breast, the more likely it is that a cancer will be hidden by the tissue. “Normal breast tissue can both hide a cancer and mimic a cancer,” says Dr. Zeb. In addition to an annual mammogram other imaging methods including a breast ultrasound and a breast MRI can be used for women with dense breast tissue.

Myth #5: I had a normal mammogram last year, so I don’t need another one this year.

Fact: Mammography is detection, not prevention. “Having a normal mammogram is great news, but it does not guarantee that future mammograms will be normal,” says Dr. Zeb. "Having a mammogram every year increases the chance of detecting the cancer when it is small and when it is most easily treated which also improves survival."

Myth #6: My doctor didn’t tell me I needed a mammogram, so I cannot schedule an exam.

Fact: You do not need your doctor to write you a prescription or complete an order form for you to have a screening mammogram. “The recommendation is that if you are a woman from age 40 on, you should have a mammogram every year, even if your doctor forgets to mention it,” says Dr. Zeb. Women can self-refer to make an appointment for their annual mammogram for earlier detection of breast cancer.

Breast BiopsyBreast ScanBreast Self-AwarenessBreast Ultrasound

Dr Nora Pashayan, from University College London, said: "Breast cancer screening prevents deaths from breast cancer in some women. On the other hand, not all cancers picked up by screening would result in death prevention and others won't be picked up by screening at all."

NHS

Screening for breast cancer with mammograms shows a big difference in the U.S. and U.K. In the US, yearly screening is recommended after age 40. In the UK, screening is recommended every 3 years for women age 50-70.

Mammogram

Mammogram

Prostate Cancer

Prostate Cancer

Prostate cancer on a site devoted to women? This is for your partner or loved ones.

The risk of developing prostate cancer increases with age, but that doesn’t mean it’s a disease that only affects old men. Prostate cancer is the second most common cancer in men worldwide. Men who are black, and men who have a family history (a brother or father with prostate cancer), are 2.5x more likely to get prostate cancer.

Signs and symptoms

- A need to urinate frequently, especially at night

- Difficulty starting urination or holding back urine

- Weak or interrupted flow of urine

- Painful or burning urination

- Difficulty in having an erection

- Painful ejaculation

- Blood in urine or semen

- Frequent pain or stiffness in the lower back, hips, or upper thighs

EARLY DETECTION IS KEY.

The difference between early detection and late detection can be life and death.

IF DETECTED EARLY 98% chance of survival beyond 5 years.

IF DETECTED LATE 26% chance of survival beyond 5 years.

When detected early, prostate cancer survival rates are better than 98%. Find it late, and those survival rates drop below 26%.

If you’re 50, you should be talking to your doctor about PSA testing. If you’re black, you need to start that conversation at 45. And if you have a brother or father with prostate cancer in their history, do it at 45.

Staging and Treatment

There are 2 types of staging for prostate cancer:

- Clinical staging. This is based on the results of DRE, PSA testing, and Gleason score (see “Gleason score for grading prostate cancer” below). These test results will help determine whether x-rays, bone scans, CT scans, or MRI are also needed. If scans are needed, they can add more information to help the doctor figure out the clinical stage.

- Pathologic staging. This is based on information found during surgery, plus the laboratory results, referred to as pathology, of the prostate tissue removed during surgery. The surgery often includes the removal of the entire prostate and some lymph nodes. Examination of the removed lymph nodes can provide more information for pathologic staging.

Gleason score for grading prostate cancer

Prostate cancer is also given a grade called a Gleason score. This score is based on how much the cancer looks like healthy tissue when viewed under a microscope. Less aggressive tumors generally look more like healthy tissue. Tumors that are more aggressive are likely to grow and spread to other parts of the body. They look less like healthy tissue.

The Gleason scoring system is the most common prostate cancer grading system used. The pathologist looks at how the cancer cells are arranged in the prostate and assigns a score on a scale of 3 to 5 from 2 different locations. Cancer cells that look similar to healthy cells receive a low score. Cancer cells that look less like healthy cells or look more aggressive receive a higher score. To assign the numbers, the pathologist determines the main pattern of cell growth, which is the area where the cancer is most obvious and looks for another area of growth. The doctor then gives each area a score from 3 to 5. The scores are added together to come up with an overall score between 6 and 10.

Patients with a higher Gleason score may need treatment that is more intensive, even if the cancer is not large or has not spread.

- Gleason X: The Gleason score cannot be determined.

- Gleason 6 or lower: The cells are well differentiated, meaning they look similar to healthy cells.

- Gleason 7: The cells are moderately differentiated, meaning they look somewhat similar to healthy cells.

- Gleason 8, 9, or 10: The cells are poorly differentiated or undifferentiated, meaning they look very different from healthy cells.

Gleason scores are often grouped into simplified Grade Groups:

- Grade Group 1 = Gleason 6

- Grade Group 2 = Gleason 3 + 4 = 7

- Grade Group 3 = Gleason 4 + 3 = 7

- Gleason Group 4 = Gleason 8

- Gleason Group 5 = Gleason 9 or 10

Treating prostate cancer

Treatment options are many and varied. Testing still can’t answer lots of key questions about disease aggression, prognosis and progression.

If you have been diagnosed with prostate cancer, it's important to keep in mind that many prostate cancers are slow growing and may not need surgery or other radical treatment.

Treatment options include:

- Active Surveillance

- Prostatectomy

- Radiotherapy

- Hormone Therapy

- Chemotherapy

Choosing a treatment for prostate cancer

Aim to be ok with the treatment decision you make, take risks and benefits into consideration.

Learn what you can, make use of the quality services and resources available. When making treatment decisions the following is recommended:

- Make a decision after a treatment recommendation from a multi-disciplinary meeting (where available). This meeting would ideally consist of input from the following specialists: urologists, radiation oncologists, medical oncologists, radiologist, nursing and allied health.

- Seek a second opinion for a recommended treatment option that is right for you, from both a urologist as well as a radiation oncologist.

- Enquire as to whether a specialist is part of a quality improvement audit, such as a registry.

- Utilise the cancer support services available in your country to increase your levels of information and understanding around treatment options, and potential side effects. Phone Prostate Cancer UK specialist nurses on 0800 074 8383 or visit their website.

- Approach your GP if you have concerns or want a second opinion.

Ongoing side effects of prostate cancer treatment

Depending on the treatment you undergo, you may experience some of the following:

- Incontinence (involuntary leakage of urine)

- Erectile dysfunction (difficulty achieving or maintaining an erection)

- Weight gain due to hormone therapy

- Depression

These side effects have different durations for different people.

Because a side effect of treatment may include erectile dysfunction, prostate cancer can have a serious impact on intimate relationships. As many people who have been through the journey will tell you, prostate cancer isn’t just a man’s disease, it’s a couple’s disease. Make sure you involve your partner as you think through the various treatment options.

PSA Screening

The PSA test is a blood test used primarily to screen for prostate cancer.

The test measures the amount of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) in your blood. PSA is a protein produced by both cancerous and noncancerous tissue in the prostate, a small gland that sits below the bladder in men.

PSA is mostly found in semen, which also is produced in the prostate. Small amounts of PSA ordinarily circulate in the blood.

The PSA test can detect high levels of PSA that may indicate the presence of prostate cancer. However, many other conditions, such as an enlarged or inflamed prostate, can also increase PSA levels. Therefore, determining what a high PSA score means can be complicated.

There is a lot of conflicting advice about PSA testing. To decide whether to have a PSAtest, discuss the issue with your doctor, considering your risk factors and weighing your personal preferences.

Why it's done

Prostate cancer is common, and a frequent cause of cancer death. Early detection may be an important tool in getting appropriate and timely treatment.

Men with prostate cancer may have elevated levels of PSA. However, many noncancerous conditions also can increase the PSA level. The PSA test can detect high levels of PSA in the blood but doesn't provide precise diagnostic information about the condition of the prostate.

Results

Results of PSA tests are reported as nanograms of PSA per milliliter of blood (ng/mL). There's no specific cutoff point between a normal and abnormal PSA level. Your doctor might recommend a prostate biopsy based on results of your PSA test.

Variations of the PSA test

Your doctor might use other ways of interpreting PSA results before deciding whether to order a biopsy to test for cancerous tissue. These other methods are intended to improve the accuracy of the PSA test as a screening tool.

Researchers continue to investigate variations of the PSA test to determine whether they provide a measurable benefit.

Variations of the PSA test include:

- PSA velocity. PSA velocity is the change in PSA levels over time. A rapid rise in PSA may indicate the presence of cancer or an aggressive form of cancer. However, recent studies have cast doubt on the value of PSA velocity in predicting a finding of prostate cancer from biopsy.

- Percentage of free PSA. PSA circulates in the blood in two forms — either attached to certain blood proteins or unattached (free). If you have a high PSA level but a low percentage of free PSA, it may be more likely that you have prostate cancer.

- PSA density. Prostate cancers can produce more PSA per volume of tissue than benign prostate conditions can. PSA density measurements adjust PSA values for prostate volume. Measuring PSA density generally requires an MRI or transrectal ultrasound.

NHS

There is an informed choice programme, called prostate cancer risk management, for healthy men aged 50 or over who ask their GP about PSA testing. It aims to give men good information on the pros and cons of a PSA test.

If you're a man aged 50 or over and decide to have your PSA levels tested, you can have it performed for free through the NHS.

Other Tests

The PSA test is only one tool used to screen for early signs of prostate cancer. Another common screening test, usually done in addition to a PSA test, is a digital rectal exam.

Neither the PSA test nor the digital rectal exam provides enough information for your doctor to diagnose prostate cancer. Abnormal results in these tests may lead your doctor to recommend a prostate biopsy.

During this procedure, samples of tissue are removed for laboratory examination. A diagnosis of cancer is based on the biopsy results.

Colon Cancer

Colon Cancer

From the Mayo Clinic

Colon cancer is a type of cancer that begins in the large intestine (colon). The colon is the final part of the digestive tract.

Colon cancer typically affects older adults, though it can happen at any age. It usually begins as small, noncancerous (benign) clumps of cells called polyps that form on the inside of the colon. Over time some of these polyps can become colon cancers.

Polyps may be small and produce few, if any, symptoms. For this reason, doctors recommend regular screening tests to help prevent colon cancer by identifying and removing polyps before they turn into cancer.

If colon cancer develops, many treatments are available to help control it, including surgery, radiation therapy and drug treatments, such as chemotherapy, targeted therapy and immunotherapy.

Colon cancer is sometimes called colorectal cancer, which is a term that combines colon cancer and rectal cancer, which begins in the rectum.

Symptoms

Signs and symptoms of colon cancer include:

- A persistent change in your bowel habits, including diarrhea or constipation or a change in the consistency of your stool

- Rectal bleeding or blood in your stool

- Persistent abdominal discomfort, such as cramps, gas or pain

- A feeling that your bowel doesn't empty completely

- Weakness or fatigue

- Unexplained weight loss

Many people with colon cancer experience no symptoms in the early stages of the disease. When symptoms appear, they'll likely vary, depending on the cancer's size and location in your large intestine.

Causes

Doctors aren't certain what causes most colon cancers.

In general, colon cancer begins when healthy cells in the colon develop changes (mutations) in their DNA. A cell's DNA contains a set of instructions that tell a cell what to do.

Healthy cells grow and divide in an orderly way to keep your body functioning normally. But when a cell's DNA is damaged and becomes cancerous, cells continue to divide — even when new cells aren't needed. As the cells accumulate, they form a tumor.

With time, the cancer cells can grow to invade and destroy normal tissue nearby. And cancerous cells can travel to other parts of the body to form deposits there (metastasis).

Risk factors

Factors that may increase your risk of colon cancer include:

- Older age. Colon cancer can be diagnosed at any age, but a majority of people with colon cancer are older than 50. The rates of colon cancer in people younger than 50 have been increasing, but doctors aren't sure why.

- African-American race. African-Americans have a greater risk of colon cancer than do people of other races.

- A personal history of colorectal cancer or polyps. If you've already had colon cancer or noncancerous colon polyps, you have a greater risk of colon cancer in the future.

- Inflammatory intestinal conditions. Chronic inflammatory diseases of the colon, such as ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease, can increase your risk of colon cancer.

- Inherited syndromes that increase colon cancer risk. Some gene mutations passed through generations of your family can increase your risk of colon cancer significantly. Only a small percentage of colon cancers are linked to inherited genes. The most common inherited syndromes that increase colon cancer risk are familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) and Lynch syndrome, which is also known as hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC).

- Family history of colon cancer. You're more likely to develop colon cancer if you have a blood relative who has had the disease. If more than one family member has colon cancer or rectal cancer, your risk is even greater.

- Low-fiber, high-fat diet. Colon cancer and rectal cancer may be associated with a typical Western diet, which is low in fiber and high in fat and calories. Research in this area has had mixed results. Some studies have found an increased risk of colon cancer in people who eat diets high in red meat and processed meat.

- A sedentary lifestyle. People who are inactive are more likely to develop colon cancer. Getting regular physical activity may reduce your risk of colon cancer.

- Diabetes. People with diabetes or insulin resistance have an increased risk of colon cancer.

- Obesity. People who are obese have an increased risk of colon cancer and an increased risk of dying of colon cancer when compared with people considered normal weight.

- Smoking. People who smoke may have an increased risk of colon cancer.

- Alcohol. Heavy use of alcohol increases your risk of colon cancer.

- Radiation therapy for cancer. Radiation therapy directed at the abdomen to treat previous cancers increases the risk of colon cancer.

- Vitamin D deficiency. in 1980, Garland and Garland first proposed a link between cancer and vitamin D from observations of higher colon cancer mortality in higher latitudes and areas with less solar radiation. This has been confirmed by multiple studies.

Staging, Treatment

The process used to find out if cancer has spread within the colon/rectum or to other parts of the body is called staging. Staging is important because it helps determine the best treatment plan.

Prevention and Screening

Prevention

Screening colon cancer

Doctors recommend that people with an average risk of colon cancer consider colon cancer screening around age 50. But people with an increased risk, such as those with a family history of colon cancer, should consider screening sooner.Several screening options exist — each with its own benefits and drawbacks. Talk about your options with your doctor, and together you can decide which tests are appropriate for you.

Lifestyle changes to reduce your risk of colon cancer

You can take steps to reduce your risk of colon cancer by making changes in your everyday life. Take steps to:

- Eat a variety of fruits, vegetables and whole grains. Fruits, vegetables and whole grains contain vitamins, minerals, fiber and antioxidants, which may play a role in cancer prevention. Choose a variety of fruits and vegetables so that you get an array of vitamins and nutrients.

- Drink alcohol in moderation, if at all. If you choose to drink alcohol, limit the amount of alcohol you drink to no more than one drink a day for women and two for men.

- Stop smoking. Talk to your doctor about ways to quit that may work for you.

- Exercise most days of the week. Try to get at least 30 minutes of exercise on most days. If you've been inactive, start slowly and build up gradually to 30 minutes. Also, talk to your doctor before starting any exercise program.

- Maintain a healthy weight. If you are at a healthy weight, work to maintain your weight by combining a healthy diet with daily exercise. If you need to lose weight, ask your doctor about healthy ways to achieve your goal. Aim to lose weight slowly by increasing the amount of exercise you get and reducing the number of calories you eat.

- Maintain Vitamin D levels. Vitamin D deficiency is highly associated with colon cancer. Keep vitamin D levels above 30 ng/ml and ideally above 40

Colon cancer prevention for people with a high risk

Some medications have been found to reduce the risk of precancerous polyps or colon cancer. For instance, some evidence links a reduced risk of polyps and colon cancer to regular use of aspirin or aspirin-like drugs. But it's not clear what dose and what length of time would be needed to reduce the risk of colon cancer. Taking aspirin daily has some risks, including gastrointestinal bleeding and ulcers.These options are generally reserved for people with a high risk of colon cancer. There isn't enough evidence to recommend these medications to people who have an average risk of colon cancer.If you have an increased risk of colon cancer, discuss your risk factors with your doctor to determine whether preventive medications are safe for you.

From the NHS:

Screening for people at high risk of bowel cancer

People with some conditions have a higher risk of getting bowel cancer at a younger age than usual. They might have screening earlier than the normal NHS bowel cancer screening programme.

.

If you are not in a high risk group

There's no NHS screening available outside the age range covered by the UK bowel cancer screening programmes if you don't have a higher than average risk of bowel cancer.

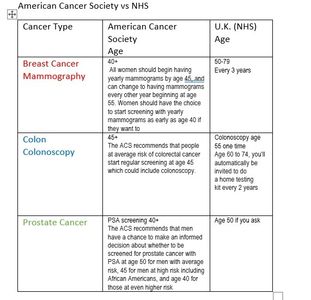

Screening Recommendations

Recommendations for Screening

The table compares screening recommendations from the American Cancer Society with the NHS

Vitamin D and Cancer

Vitamin D

All Cancer Estimates

All Cancer Estimates

Considerable data indicates a link between low vitamin D levels and some types of cancer. The first human evidence to suggest a relationship between vitamin D and cancer prevention came from epidemiological studies which suggested increased sunlight (UVB) exposure or populations living in lower latitudes had a lower incidence of colon cancer. Vitamin D compounds have now been found to have a strong anti-tumor effect, and help potentiate the anti-tumor actions of many more traditional anticancer agents. This has been found to be helpful for at a number of cancers including breast, prostate, skin (malignant melanoma) as well as lung,ovary, breast, bladder, pancreas and some brain cancers. This is attributed to the important role of vitamin D in immunity, regulating inflammation and antiangiogenic effects.

All Cancer Estimates

All Cancer Estimates

All Cancer Estimates

A number of studies have shown increased risk of some cancers with vitamin D deficiency. The benefit of vitamin D supplementation for prevention of cancer is less clear. This may partly because vitamin D levels were not high enough- the benefit seems most apparent for levels > 40 ng/ ml